Berlin: Land of Museums, Churches and Theaters

I’m happy to report that after several nice days full of Berlin adventures, the city has stopped making me nervous. And I think a lot of that has to do with the language slowly coming back to life in my brain—I noticed the other night, after going to the theater and hearing a play in German, I was thinking in German again, something I haven’t done in lo these many years. It probably has something to do with so much of my Wagner agenda for this trip clicking into place, now that I’m here in Germany. And more than that, it probably has to do with Berlin being one of the world’s greatest cities, and a joy for anyone to explore.

Where to begin? Tough question, because it’s vast. Berlin’s incredible size reminds me only of New York and London, among sprawling cities we’re I’ve walked my feet to pulp. (Berlin has in fact a great mass transit system; more on that later.) I’ll begin where the last blog left off—I posted a photo I took of the Berliner Dom at night, seen from the fountain, the big cathedral on the main drag, Unter den Linden. It was made by Kaiser Wilhelm I in the 1890s, and is in that bric-brac fin de siècle (what you’d call in Yiddish onge patchket) allied with a massive Teutonic monumentalism. Thus, the organ features more than 7000 pipes:

And to reach the top of the Dom you climb forever and ever. But you get a nice view up there, assuming it’s a decent day; the Dom is on Museum Insel, a small island in the River Spree which is covered in museums and monuments. From the dome, to the north and a smidgen east, in the center of this photo, the gold hemisphere you see is the dome of the main Berlin synagogue:

And, closer up, that synagogue may be worth a visit if you get particularly interested in the Berlin Jewish community. I was, and here’s the story: the synagogue was built in the mid-19th century as Berlin became a magnet for Jews from all over Germany and eastern Europe. It held services up to 1943, at which point the Nazis took it over completely; and it was largely destroyed by the bombing before the end of the war. But so were most of the Jews in Berlin, and only a few stayed after 1945, so it wasn’t until the 80s that they started dealing with the synagogue. They’ve reconstructed the front façade on Oranienburger Str., with the beautiful dome:

But behind, where the synagogue proper used to be, is just an open field. (There’s a mediocre museum with some stuff saved from the rubble beneath the dome.) So it’s not necessarily worth the trip. (The Schwules Museum also turned out to be a big bust. Oh—poor choice of words, that.) If you’re interested in the Berlin Jewish Community—or even if you’re not—you really ought to go to the striking Jüdisches Museum Berlin, which is a ways south of Museum Insel. I got there by walking down a little alley named for one of my all-time favorite authors:

Bet you didn’t know Hoffmann was all those things listed on the sign (Dichter, Komponist, Maler und Kammergerichtsrat). Well, it’s true. Anyway, the Jüdisches Museum opened in 2001; it was designed by Daniel Liebeskind, who built a truly bizarre space. See the photo below. The large building to the right houses the main permanent exhibit and also the space for temporary exhibits; but there’s no doors in that building (of course I had to discover this fact the hard way, walking all around the block in the pouring rain!). You enter through a much more traditional building next door, go downstairs, and find yourself in three long intersecting hallways laid out something like a letter ‘A’ if the middle line kept going on either side. One Axis takes you to the main building; a second, the Axis of the Holocaust, takes you past memorabilia of Holocaust victims to the big white blur in the middle of the photo—that’s an empty concrete tower, a memorial to those murdered in the Holocaust, and at the end of that axis you can (if you choose) enter the bottom of the tower, which is a cold, dark space, reminiscent of prison or death—with one glimpse of light, way high above, dazzling even when it’s raining out. The third line of the ‘A’ is the Axis of Exile, with memorabilia of Jews who lost their homes in recent diasporas; it leads to the ‘Garden of Exile’ a sort of chess board with 48 concrete pillars (you see the tops of the pillars poking above the ground in the center of the picture, with willows growing from them) standing for the year 1948, when Israel was formed. Wandering through this pillared space is disorienting, as is being exiled; although I did notice some kids having fun hiding behind the columns and surprising one another while I was in there.

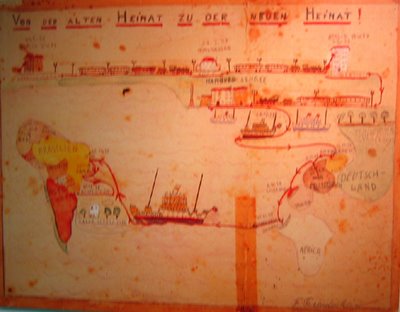

Speaking of kids and exile, along the Axis of Exile I had to grab a photo of this reproduction: an 11-year old boy’s family left Germany for Uruguay in the 1930s, and he kept this record of his journey “Von der alten Heimat zu der neuen Heimat” (from the old homeland to the new homeland) on his trip, with every form of transportation they used at the top and a vague map of their route below: an early trip blog!

The permanent exhibition at the Jewish Museum Berlin is about Jewish life in Germany from the Dark Ages up to the rise of National Socialism. (The more recent stuff is well-covered by many other institutions! Among them are the Deutsches Historisches Museum, whose current exhibition on German poster art/advertising over the last 130 years follows this story—and is well worth a gander.) The special exhibition at the Jewish Museum, yesterday, was a “Happy 150th Birthday, Siegmund Freud” suite, complete with an enormous, room-sized birthday cake upon which puppets acted out every chapter of Freud’s biography, from the scene where the young Ziggy (the puppet for the little boy already had a beard and big round “Where’s Waldo” glasses) stumbles upon his mother naked to the hypnotism of Anna O and her dream:

I gotta say, I loved this cake—and I didn’t even get to eat a slice. (Nor am I much of a Freud fan.) It reminded me of something I once tried to do in a Seattle Opera Parsifal publication, a timeline of Richard Wagner’s life in the style of a boardgame, ie “Help Richard find his way to the Temple of the Holy Grail!” See, kids? Who’d have thought learning could be so much fun?

I was reminded of Wagner in the Jewish Museum particularly on the Axis of Exile, since Wagner’s life is all about exile—he was a German, and for most of his life there wasn’t a Germany, and even so for the most productive years of his life, due to his political activities, he was exiled from what Germany there was.

We saw more about exile this morning at the Haus am Checkpoint Charlie, a very grass-roots museum about the Berlin Wall, and the separation of East and West Berlin and East and West Germany, and nonviolent resistance in the 20th century. This experience I also recommend highly—it’s a story I thought I knew, but I didn’t know the half of it, the bizarre, dangerous, and ingenious ways people from the east invented to escape to the west and the well-documented ethical conundrum experienced by the soldiers who worked the wall, who were told ‘shoot to kill’ any time someone tried to escape, but who (like Vader’s stormtroopers) most of the time seemed to have terrible aim. As an American, the experience of the divided Germany reminds me of our Civil War—a house divided against itself cannot stand and all that—but of course it’s the opposite experience because no one in Germany WANTED to be divided in two. The scars of the American Civil War are still healing, and I’m sure the same will be true a hundred years from now in Germany. On the other hand, there are plenty of teenagers (swarming every museum and theater I’ve been to since I got here), some of whom now were born AFTER the wall fell. What do they think of it? What would RW have thought of it? Oy vey!

A few other Wagner-related experiences I’ve had these last couple of days, and then I’ll end this post. The problem is, since Wagner basically engorged the entire world and made it strangely his, it’s possible for everything in life to relate to Wagner. You think I’m kidding, but I’m not. This afternoon I managed to spend a little time at the Staatliche Museum zu Berlin Gemäldegalerie (Painting Gallery) studying the current exhibition on “Albrecht Dürers Mutter”. This exhibition centers on a drawing the great Renaissance woodcut and sketch artist and painter Dürer did of his mother shortly before she died (right); it’s a wonderfully thorough exhibition which gathers hundreds of images of old women, old men, beauty, ugliness, and death from Dürer’s time. He is far and away the greatest artist of them all, and it’s his incredible humanity and love for his mother which still shines brightly from this drawing. The Wagner connection, of course, is the prominent mention of Dürer in Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Wagner’s greatest opera and his love letter to “Heilige Deutsche Kunst”, Holy German Art.

Meistersinger is his most accessible opera, despite its ridiculous length, because the music sounds like Bach and the story is like a Shakespeare comedy. With that in mind, I visited two theaters these last two days: this evening, the Berliner Philharmoniker Kammermusiksaal, the smaller of the two Berlin Phil rooms (it seats 1500, in the round) to hear the Berliner Figuralchor and Berlin Baroque, under the fingers (no baton) of the not-very-charismatic Gerhard Oppelt and a quartet of soloists, doing the Bach B-Minor Mass. What a piece! The closest Bach ever came to writing an opera, I’ve always asserted. The Berliner Baroque is a small ensemble reminiscent of Seattle Baroque (and where are THEY now?) who play on period instruments—for this mass, we had three old-timey violins with weird bows, two old-timey flutes that sound kind of like recorders, three wonderful old-timey oboes, a valveless horn (amazing work from that guy, who had to do it all with his lips and his hand in the bell), three trumpets, continuo of cello, lute, and organ, and old-timey timani which seem to be even harder to keep in tune than modern timpani. The singers weren’t really opera singers, but rather the kind of people who specialize in lieder or concerts with orchestra. The countertenor who sang the alto part, Alex Potter, was pretty good. Anyways, it was great to be there, and to hear this piece I’ve always loved. And which reminds me of Meistersinger.

I checked the schedules at Berlin’s three opera companies this week, but there wasn’t anything I HAD to hear and frankly, after last week, I figured I could take a break from opera. So I went instead to the theater; to Vaganten Bühne, near where I’m staying at Savingy Platz, to see a play I know extremely well in English: Shakespeares Sämtliche Werke (Leicht Gekürzt) (The Complete Works of William Shakespeare—Abridged). If you don’t already know this riotous farce, think “Jon ‘n’ Perry get a bunch of high school kids to act out the Complete Works of Richard Wagner in a half an hour” and you’ve got the right idea—infotainment, even more so than that Freud Birthday Cake. I was surprised and pleased to see that the translator, Dorothea Renckhoff, has taken a few liberties with the immortal words of Messrs. Long, Singer, and Winfield: the Troilus and Cressida gag is gone, the Macbeth section expanded to feature Lady M, and the biography of Shakespeare gag altered for obvious reasons. (In the English version, the very confused actor reading Shakespeare’s bio from a bunch of index cards ends up saying things like “Shakespeare annexed the Sudetenland and the invaded Poland; in 1945 he committed suicide with his mistress, Eva Braun” but in Germany he moved to Weimar, lived opposite Goethe, and penned the immortal words of the “Ode to Joy” instead, as did Schiller.) Since Wagner idolized Shakespeare, wanted to be the next Shakespeare (far more than he ever wanted to be a composer), and spent much of his childhood and young adulthood working for low-budget theater companies like the one which presented this masterpiece tonight, I felt it highly incumbent upon me to attend—after all, as you know, I SEEK RICHARD!

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home